Intro

Have you ever:

-

regretted that you only remember some bare trivia from a course or a book that you studied several months ago? Or maybe even stuff from university/college that you wish you’d recall now?

-

constantly annoy yourself with looking up some implementation detail, API definition or another fact, that you need every couple of weeks, but juuuust manage to slip your mind the next time you require it?

-

feel like learning new stuff (perhaps to progress beyond your current job) is a Sisyphean task that doesn’t net you anything?

If so, than this series of articles is for you.

The Perils of Ad-Hoc Learning

The nice thing about living now is having slightly more free time for your basic non-survival needs. The absolutely scary thing, in turn, is that the amount of information you have access to, and can gain, is simply overwhelming. Understandably this becomes even worse for IT professionals, what with a new library/framework coming out every week [1].

Of course, a lot of this information is fire-and-forget. Another portion you use day to day and, by this virtue, remember without any problems.

What’s left can be divided into two broad categories.

One is knowledge that you use in irregular, but relatively frequent intervals. An example would be an API quirk that you keep re-reading about every couple of weeks. Irritating, isn’t it? Also wasteful.

The other contains "core" knowledge - stuff that you’re not necessarily using directly, but nevertheless benefit from recalling it readily. Forgetting this kind of information is much more insidious - you just end up doing stuff less effectively; or, perhaps one day you suddenly realize that you completely forgot all the things you wanted to learn from the course you did half a year ago.

Spaced Repetition - a solution

Obviously no one is going to sit around every day working on remember their cumulatively growing knowledge by rote.

But there are shortcuts to do something very similar much more efficiently.

The concept of Spaced Repetition offers one such shortcut. There are many implementations exploiting the idea, but they all boil down to taking advantage of particularities of the human brain in order to achieve effective recall of various facts and concepts, with relatively minimal effort.

An SR-based approach

One such implementation is Anki. It’s flashcard-based spaced repetition software. Its documentation can be found here, and it’s available for download on:

The tl;dr version of the process of working with flashcards and SRS looks like this:

-

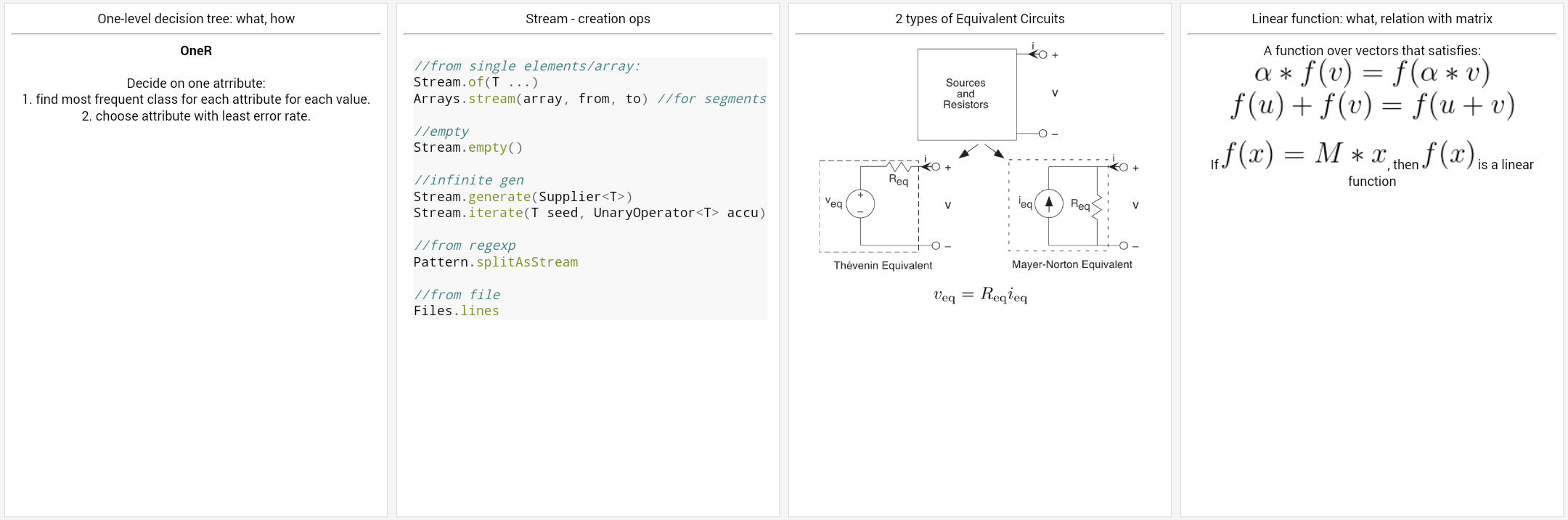

you create a flashcard. In the simplest version it’s a note with two faces: the prompt for what you want to learn, and the thing you want to learn. Here’s a couple of examples.

-

after several initial repetitions, Anki prompts you with the cards, in increasing time intervals: initially a couple of days, then a couple of weeks, months, and so on. At each repetition, when viewing the answer, you are prompted to choose one of the following options:

-

"Again" which means you forgot about the entry, and need to reset the learning process,

-

"Good" meaning you have good recollection, i.e. the vanilla option,

-

"Hard" implying thatas you’ve sorta learned, but aren’t quite confident, leading to a shorter time to repetition,

-

"Easy" that tells the system to extend the time interval to a greater extent than with "Good".

-

As you have probably figured it out, the biggest benefit from this system is that the time intervals are managed automatically, and you get automatic reminders to repeat your cards (which is especially useful if you install the mobile client).

Coming Up

In the second episode of this series, we will talk about a learning scheme developed empirically by Yours Truly, that takes advantage of Anki when acquiring technical (and other) knowledge.

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Email