Series' Table of Contents

Unfortunately, just after the first installment of this series, I’ve involved myself in another side-project, which will probably be released soon. But hey, that’s no excuse to at least make a small update in the meantime, to keep the ball rolling, right?

Scope

Desiderata

As mentioned in the first post, the next step should be defining our scope. This basically boils down to making our exploration of the streaming paradigm as efficient as practicable, specifically identifying problems intrinsic to game programming.

One of those is efficient resource allocation. Games need to spawn and remove potentially large numbers of object quickly, and without taxing the memory of the device. For JVM-made games, Android device limits would probably serve as the most prominent example in recent years[1]. Game engines like libgdx mitigate this problem by employing pools of mutable data structures (which reduces the number of created objects, and hence GC time), among other tricks.

Another issue is smooth rendering of the game’s updates. Enjoyment drops sharply if the game becomes visibly choppy.

A related problem is responsiveness to player input. Smooth FPS gives little consolation if the player remains constantly frustrated while unable to react in time to the unfolding events.

To sum up…

We would like to have a game that:

-

requires relatively quick player reaction (so e.g. no turn-based games),

-

has a lot of events happening at any given moment,

-

and employs a large number of entities to do so.

Recall also one of our initial assumptions: mistakes will be made prominent (and prominently made), including potentially avoidable ones, in order to showcase them and their solutions.

First sketches

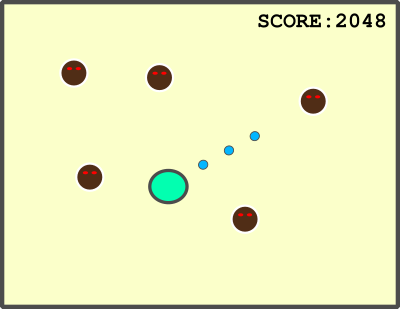

Obviously, we want some kind of an arcade game, somewhat close in style to a shoot’em up, even drifting into bullet hell territory[2].

For starters, we want some sort of controllable character, multiple, respawning enemies, and some sort of score meter (which will help us gauge the rate of updates).

Here’s a veeery rudimentary sketch of how the game will look like at the beginning:

Of course, we’ll keep adding stuff as we go along, but we already have more than enough work to do.

Up Next

In the following episode we’ll finally see some code. We’re going to define the boilerplate skeleton of our application, and create an Akka Streams source that allows to react to game state updates.

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Email